Mary and Max: Letters in Clay and Loneliness

Adam Elliot’s Mary and Max (2009) turns clay, loneliness, and absurdity into a meditation on friendship. It’s stop-motion as soul motion—an offbeat elegy for connection in a world allergic to sincerity.

In a world of immaculate pixels and algorithmic storytelling, Adam Elliot remains gloriously analog. He sculpts not just clay but the frailty of being human. Born in rural Australia in 1972, Elliot grew up on a farm among siblings and parrots, surrounded by the quiet monotony that later became the heartbeat of his art. He studied photography, painting, and poetry before turning to animation—a medium that rewards the patient and the haunted.

Mary and Max

2009 / 92m

Elliot’s early shorts—Uncle (1996), Cousin (1998), and Brother (1999)—are intimate portraits of small tragedies. Each film feels like an entry in a family diary written by someone who still loves the people he’s exposing. They balance humor and heartbreak on a knife’s edge, their stillness inviting the audience to fill the silence with recognition. These miniature worlds already carried the themes that would define his career: isolation, absurdity, and the fragile dignity of the misfit.

Then came Harvie Krumpet (2003), a clay biography of perpetual bad luck. The story of a Polish émigré cursed with Tourette’s syndrome, a missing testicle, and relentless optimism, it’s both grotesque and tender—a tone only Elliot could sustain. The film won him an Oscar, but what mattered more was how it refined his voice: compassionate, absurd, unflinchingly human. Elliot doesn’t mock his characters’ strangeness; he sanctifies it.

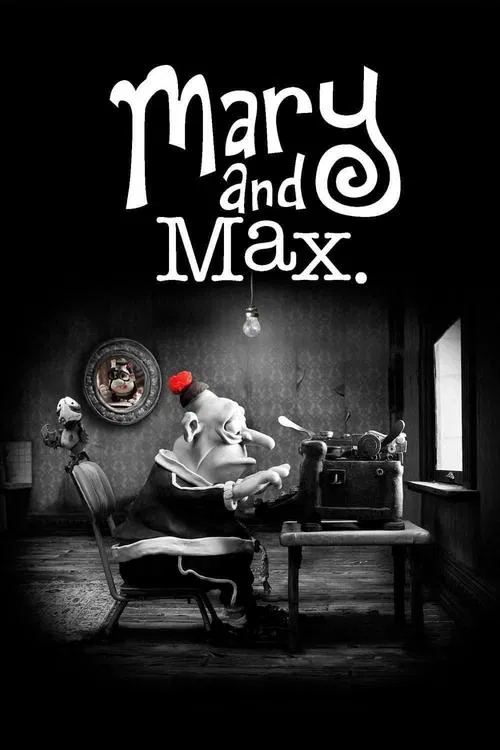

Six years later, Mary and Max (2009) arrived like the full stop at the end of his thematic sentence. It’s his longest, darkest, and most generous work—a feature-length stop-motion film about friendship, mental illness, and the desperate need to be understood. Mary is a neglected Australian girl with a birthmark shaped like a teardrop; Max is an overweight New Yorker with Asperger’s syndrome. Across continents and decades, they exchange letters that become lifelines.

There’s no spoken dialogue, only narration—Barry Humphries’ voice threading the distance between them. But that absence of chatter becomes the film’s strength. The story unfolds like a long confession, or perhaps a eulogy for connection itself. Every letter they send is a plea to exist in someone else’s eyes. Elliot’s clay figures, imperfect and trembling, seem to breathe the ache of solitude.

What sets Mary and Max apart is not its technical skill—though every frame is an intricate sculpture of light and patience—but its emotional honesty. Where most animated films chase spectacle, Elliot lingers on quiet rooms and messy interiors. His clay worlds are dusty, static, almost airless; they feel inhabited by time. The camera doesn’t move to impress you. It moves like memory—slowly, carefully, afraid of breaking what it loves.

The performances give the film its pulse. Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Max is a marvel of restraint—a man trapped inside his own brilliant, bewildered mind. Toni Collette’s adult Mary, fragile and luminous, carries the weight of hope long past its expiry date. Together, they inhabit a friendship too odd for sentimentality and too pure for irony.

Elliot’s humor remains dry and surgical. He finds comedy in discomfort—the way people name their pets after dead relatives, or how a single chocolate bar can save a day. But beneath that humor lies a deep melancholy: the knowledge that most of us, like Mary and Max, are just writing letters to the void, praying someone writes back.

In Mary and Max, clay becomes flesh, and animation becomes confession. It’s a film about the geometry of empathy—how two lonely lives can align for a moment and make the world less unbearable. The lighting is dim, the palette muted, yet within that grayscale beats something incandescent. Elliot makes you forget you’re watching stop-motion at all. What you’re really watching is the anatomy of loneliness, rendered in trembling clay.

Mary and Max isn’t just an animated film. It’s a quiet miracle—funny, heartbreaking, and profoundly human. Elliot doesn’t give us heroes or villains, only people trying to understand why life feels so heavy. His world smells of dust, chocolate, and burnt letters. And when the credits roll, you realize you’ve been watching yourself all along.

A masterpiece in miniature, Mary and Max proves that even in clay, the human heart leaves fingerprints.